What’s “The Clean Architecture”? ¶

First result on Google Search says:

The Clean Architecture is a software architecture proposed by Robert C. Martin (better known as Uncle Bob).

This architecture is similar to the Onion-Hexagonal-DCI-Architecture proposed by their respective authors.

The base of this architecture is to follow and obey rules of the ‘Dependency Rule’.

Let’s extract the important bits:

- The author is Robert C. Martin

- It’s similar to other architectures:

- Onion: consists of several concentric layers interacting with each other towards the core, which is the domain.

- Hexagonal: helps shift the main focus to the business domain while spending less time on the technical aspects of it.

- Data, context and interaction (DCI): an event-driven programming paradigm, where some event triggers a use case.

- It aims to follow the ‘Dependency Rule’, which states that “dependencies can only point inwards”.w

The Theory ¶

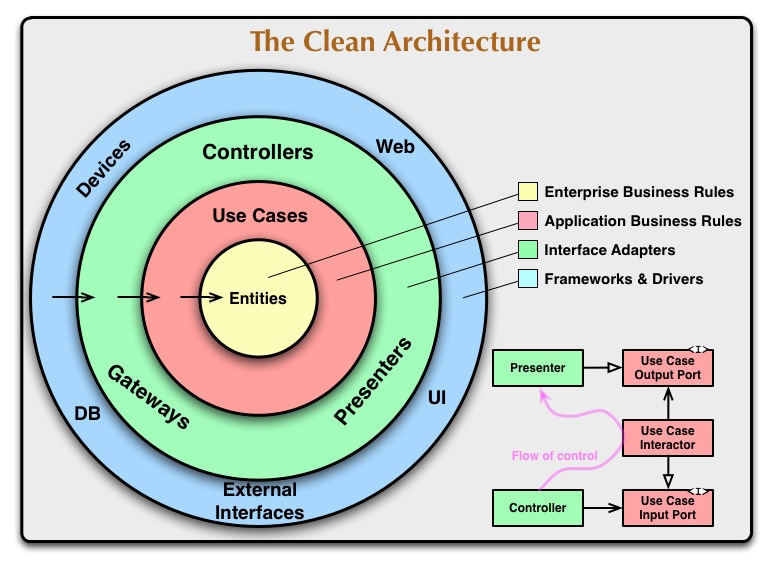

On paper, the Clean Architecture works as per this famous image:

Input comes from various sources: Web, Devices, UI, etc. Then, data is received by the controller, processed by the usecase and finally returned to the caller through the presenter.

The folder structure would look something like this:

project

|_ domain

|_ infrastructure

| |_ db

| |_ webservice

| |_ provider

|_ interface

| |_ controller

| |_ presenter

|_ usecase

|_ interactor

Domain ¶

The domain folder contains the basic domain’s entities and their repositories’ interface/contracts.

Infrastructure ¶

The Infrastructure collects all those pieces of code that know which protocols to use to retrieve and store data: third party providers, HTTP web-services, databases etc.

Interface ¶

The interface folder is the most confusing bit. It sounds like it should only contain interfaces/contracts of what is then implemented elsewhere, but the name stands for its literal definition:

Interface: a point where two systems, subjects, organizations, etc. meet and interact.

Usecase ¶

The usecase folder, finally, is the core of the business logic.

This layer contains reusable logic, that defines how data will be processed when the “user” interacts with the service.

In Practice ¶

As we all know too well, reality often differs from the beauty of the theory. Here’s a list of common patterns that are built on the idea of the Clean Architecture and branch out to a custom usage.

The all-in-one interface folder ¶

This approach drops the infrastructure folder, in favor of putting everything within the interfaces folder.

In languages that support interfaces/contracts, this creates a bit of confusion, since both interfaces and their implementations are in the same folder.

Interface is I N T E R F A C E ¶

As previously mentioned, some might debate that the interface folder should only contains interfaces/contracts, when the programming language supports it.

This approach makes the code more intuitive, since all the interfaces are within a single package/folder.

When using the interface folder this way, all the implementations are usually stored in the infrastructure.

The domain/repository civil war ¶

When the domain’s entities and their repositories were first separated from each other, this approach was born.

Usually, the repositories are moved either in the interfaces, the infrastructure or in both folders (split as interface/contract and implementation).

Useful when there are a lot of entities divided in subdomains or entities that do not require a repository.

The over-mighty usecase ¶

Ever thought the usecase folder needed to be beefier? Look no further than this approach, where both presenters and controllers are included under the usecase folder.

Putting together all the “do-er” (i.e. controller, interactor, presenter), might sound like a personal choice of style, but it’s used to collect all the input logic within the same folder.

The jack of all trades controller ¶

Usually based upon the previous variant, this one embeds the interactor and presenter logic within the controller’s. This monolithic logic creates a single and large point of processing for the input data. It works well for proof of concepts or rushed services, but it is in no mean maintainable, testable or readable.

The “yo dawg, I heard you like clean architecture…” ¶

This led to each folder of the clean architecture structure having the clean architecture structure within itself. The approach inception ensures that each folder is structured in a predictable way, but imports are extremely confusing and the “clean” aspect of the architecture is lost in the recursion.

Conclusion ¶

Whether you use it as intended or in any of its other variations, the Clean Architecture is a great paradigm and definitely worth including in your projects.

Like many other things in software engineering, it is subject to manipulation and changes. Everyone might bend it to fit their views and their style: either by improving it or simplifying it.

Both are valid options and should be taken into consideration when starting a new project.

Stay tuned for a detailed example on how a Golang projects looks like when using the Clean Architecture.